Photo by Brian McGowan / Unsplash

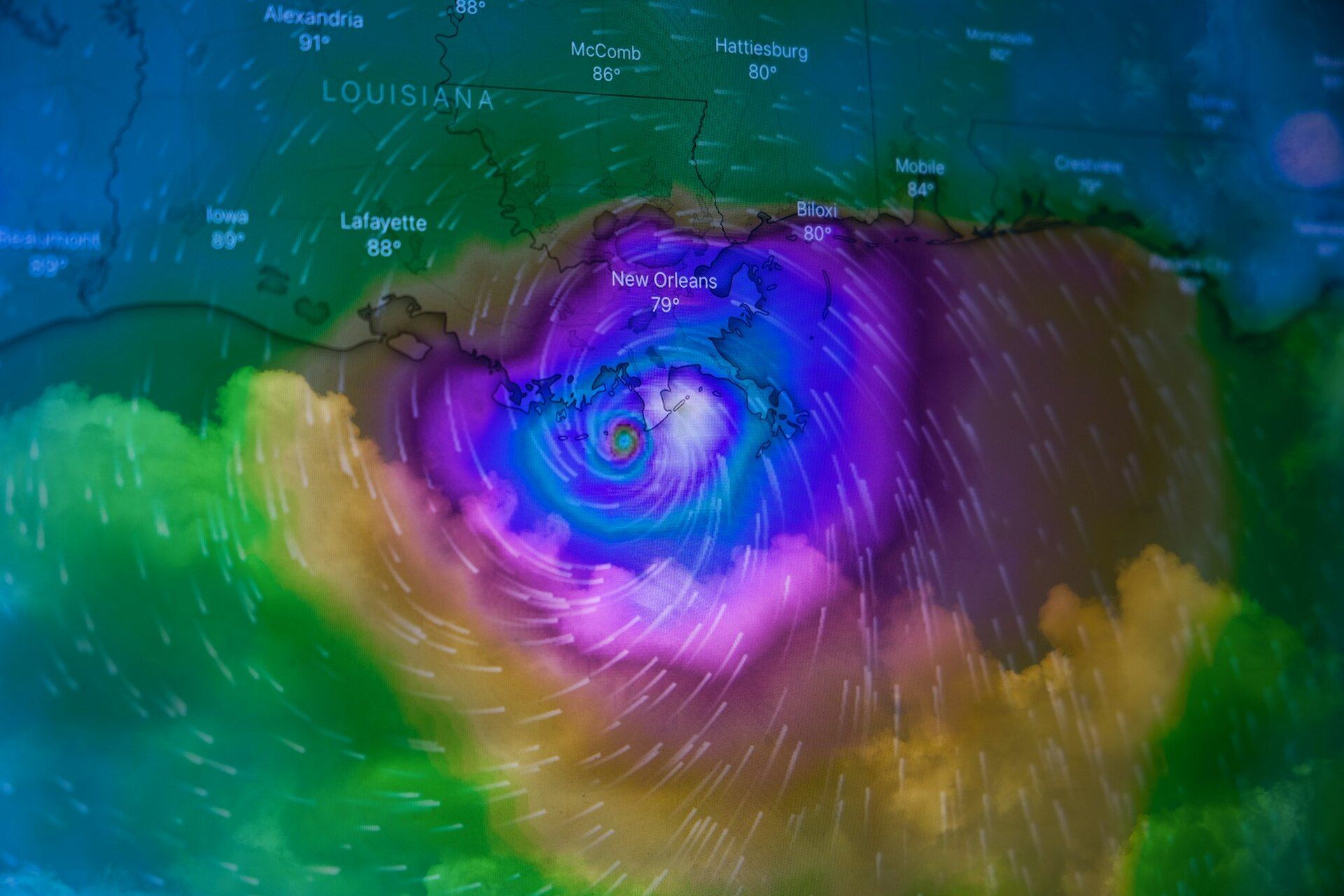

Summer in the northern hemisphere has arrived with a bang, bringing extreme weather that has already claimed lives. In early July, a flash flood of the Guadalupe River in Texas caused water to rise 26 feet in just 45 minutes, leading to the deaths of at least 120 people. Meanwhile, a massive heat dome stifled the East Coast, putting more than 147 million people in 28 states under heat alerts in early June.

Europe’s luck has been much the same, where summer storms and extreme heat have broken records. In Portugal and Spain, temperatures soared to 45 degrees C, while the Mediterranean Sea peaked at record temps, nearly 3 degrees C above average for this time of year. Heat in China has threatened rice crops, as temperatures climbed as high as 40 degrees C in some locations, raising concerns about food insecurity in the populous nation.

Yet the threat of rising heat and increasingly intense storms is only one part of a new phase of the climate crisis. Intentional institutional chaos in the United States is exacerbating the real-time effects of climate change. Higher temperatures have made the weather increasingly difficult to predict, just as the Trump administration is ramping up efforts to gut the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, along with the National Weather Service (NWS). Staff cuts in both agencies have siphoned off critical data for tracking weather, and a push to privatize them may soon put what has been free and accurate climate data behind paywalls.

This convergence has already claimed lives and will continue to do so, underlining the ongoing dismantling of interconnected systems that we’ve come to depend on, even though the threat of climate change transcends borders, sectors, and traditional policy frameworks.

The Weather is Harder to Predict

The simultaneous heat domes that have hit multiple continents so far this summer exposed a new reality: climate change is making weather both more extreme, and harder to predict at a moment when we need forecasting the most.

Research from Stanford University in 2021 shows that with every degree Celsius of warming, the window for accurate weather forecasts shrinks by several hours. For precipitation like the kind that caused the deadly Texas flooding, predictability falls by about a day for every increase of 3 degrees Celsius. As Stanford weather scientist Aditi Sheshardri told the Washington Post in 2022 about weather predictability and climate change: “colder climates are just inherently more predictable than warmer ones.”

Heat is the deadliest form of extreme weather in the US, contributing to more than 800 deaths annually. When forecasters lose even a single day of predictability for events affecting over a billion people globally, as they did during this summer’s simultaneous heat domes, the consequences ripple through every system that depends on weather warnings, from emergency evacuations to agricultural planning to power grid management.

Heat is also proving to have extensive economic consequences for everyone from gig workers, to power generation and transportation. Prolonged heat has impacted logistical chains by limiting how much a flight can carry, ‘sun-kinking’ railroad tracks, melting roads and limiting the output of wind turbines. The forecasting crisis creates what experts call "compound uncertainty"—when the tools we rely on for safety become less reliable precisely when they're most needed.

Politics Has Hobbled Weather Prediction Science

The flood disaster in Texas has put Trump's cuts to NOAA and NWS in the limelight. The U.S. president’s intentional dismantling of scientific institutions amplifies climate risk for everyone, at a moment when climate change demands a scientific and sophisticated response.

And yet, the Trump Administration’s budget proposal for 2026 calls for doubling down on the cuts by eliminating NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR). OAR is the research arm of NOAA, conducting research to predict climate change, and has been in operation since 1970. As Craig McLean, a former director of NOAA’s OAR told NPR in April this year, the cuts would “take us back to the 1950s in terms of scientific footing and the American people.” All funding for research focused on weather and climate would be cut. Yale’s Climate Connections points out that cuts to NOAA directly increase the risk of deadly weather tragedies like the one that claimed lives in Texas, though others disagree.

The Flooded Locations And Simulated Hydrographs Project (FLASH), which doubled the accuracy of flash flood warnings when implemented in 2016, was developed at NOAA's National Severe Storms Laboratory— one of the labs slated for closure under the 2026 budget plan from the administration. The proposed budget also eliminates funding for hurricane-tracking aircraft, weather balloon launches, and the satellite systems that provide real-time data to meteorologists worldwide.

While some argue that private weather services could replace NOAA, this ignores a fundamental reality: private forecasters depend entirely on the vast network of satellites, radars, and research programs that only government agencies have proven the ability to maintain.

More Investment, Not Less

Going forward, the ability to adapt weather forecasting systems to a warming world will depend not only on scientific innovation but on institutional support and long-term investment. Several international efforts are already underway. The World Meteorological Organization has called for a “Global Early Warning System” to improve forecast accuracy and disaster response, especially in vulnerable regions. The UN’s Early Warnings for All initiative, launched in 2022, wants to ensure every person on Earth is protected by early warning systems by 2027.

In the U.S., some states and regional governments are increasing their investment in hyperlocal forecasting and climate adaptation. For example, New York’s Mesonet system, a dense network of automated weather stations, offers higher-resolution data to improve local forecasting and emergency management. Researchers are also working on integrating machine learning into weather prediction, with studies showing AI models like GraphCast and FourCastNet could outperform traditional methods for short-term forecasts.

But like everything, these innovations rely on baseline data infrastructure that only large-scale, government-backed systems like NOAA and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts or ECMWF provide. Think of it like GPS–it wouldn’t exist if the government hadn’t invested in it.

As climate volatility increases due to climate change, maintaining and modernizing public weather warning systems will become crucial to managing climate change risk and enhancing weather resilience across the board. The scientific consensus is clear: adaptation to climate change not only requires better models, but sustained, coordinated, scientific data ecosystems to support them.